|

de | Thema: Theorien über kapitalistischer Krisen und Imperialismus

en |Theme: Theories on Capitalist Crises and Imperialism

fr | Théma: Théories sur des crises capitalistes et impérialisme

nl | Thema: Theorieën over kapitalistische crises en imperialisme

de | „Auch wenn eine Gesellschaft dem Naturgesetz ihrer Bewegung auf die Spur gekommen ist – und es ist der letzte Endzweck dieses Werks, das ökonomische Bewegungsgesetz der modernen Gesellschaft zu enthüllen –, kann sie naturgemäße Entwicklungsphasen weder überspringen noch wegdekretieren. Aber sie kann die Geburtswehen abkürzen und mildern.“

en | “And even when a society has got upon the right track for the discovery of the natural laws of its movement – and it is the ultimate aim of this work, to lay bare the economic law of motion of modern society – it can neither clear by bold leaps, nor remove by legal enactments, the obstacles offered by the successive phases of its normal development. But it can shorten and lessen the birth-pangs.”

fr | « Lors même qu’une société est arrivée à découvrir la piste de la loi naturelle qui préside à son mouvement – et le but final de cet ouvrage est de dévoiler la loi économique du mouvement de la société moderne – elle ne peut ni dépasser d’un saut ni abolir par des décrets les phases de son développement naturel; mais elle peut abréger la période de la gestation, et adoucir les maux de leur enfentement. »

nl | “Ook wanneer een maatschappij de natuurwet van haar ontwikkeling op het spoor is gekomen – en het uiteindelijke doel van dit werk is de onthulling van de economische ontwikkelingswet van de moderne maatschappij – kan zij de natuurlijke ontwikkelingsfase noch overslaan noch bij verordening afschaffen. Zij kan echter wel de geboorteweeën korter maken en verzachten.”

de | „Das allgemeine Resultat, das sich mir ergab und, einmal gewonnen, meinen Studien zum Leitfaden diente, kann kurz so formuliert werden: In der gesellschaftlichen Produktion ihres Lebens gehen die Menschen bestimmte, notwendige, von ihrem

Willen unabhängige Verhältnisse ein, Produktionsverhältnisse, die einer bestimmten Entwicklungsstufe ihrer materiellen Produktivkräfte entsprechen. Die Gesamtheit dieser Produktionsverhältnisse bildet die ökonomische Struktur der Gesellschaft, die reale Basis, worauf sich ein juristischer und politischer Überbau erhebt, und welcher bestimmte gesellschaftliche Bewußtseinsformen entsprechen. Die Produktionsweise des materiellen Lebens bedingt [nicht: bestimmt] den sozialen, politischen und geistigen Lebensprozeß überhaupt. Es ist nicht das Bewußtsein der Menschen, das ihr Sein, sondern umgekehrt ihr gesellschaftliches Sein, das ihr Bewußtsein bestimmt. Auf einer gewissen Stufe ihrer Entwicklung geraten die materiellen Produktivkräfte der Gesellschaft in Widerspruch mit den vorhandenen Produktionsverhältnissen oder, was nur ein juristischer Ausdruck dafür ist, mit den Eigentumsverhältnissen, innerhalb deren sie sich bisher bewegt hatten. Aus Entwicklungsformen der Produktivkräfte schlagen diese Verhältnisse in Fesseln derselben um. Es tritt dann eine Epoche sozialer Revolution ein. Mit der Veränderung der ökonomischen Grundlage wälzt sich der ganze ungeheure Uberbau langsamer oder rascher um. In der Betrachtung solcher Umwälzungen muß man stets unterscheiden zwischen der materiellen, naturwissenschaftlich treu zu konstatierenden Umwälzung in den ökonomischen Produktionsbedingungen und den juristischen, politischen, religiösen, künstlerischen oder philosophischen, kurz, ideologischen Formen, worin sich die Menschen dieses Konflikts bewußt werden und ihn ausfechten. Sowenig man das, was ein Individuum ist, nach dem beurteilt, was es sich selbst dünkt, ebensowenig kann man eine solche Umwälzungsepoche aus ihrem Bewußtsein beurteilen, sondern muß vielmehr dies Bewußtsein aus den Widersprüchen des materiellen Lebens, aus dem vorhandenen Konflikt zwischen gesellschaftlichen Produktivkräften und Produktionsverhältnissen erklären. Eine Gesellschaftsformation geht nie unter, bevor alle Produktivkräfte entwickelt sind, für die sie weit genug ist, und neue höhere Produktionsverhältnisse treten nie an die Stelle, bevor die materiellen Existenzbedingungen derselben im Schoß der alten Gesellschaft selbst ausgebrütet worden sind. Daher stellt sich die Menschheit immer nur Aufgaben, die sie lösen kann, denn genauer betrachtet wird sich stets finden, daß die Aufgabe selbst nur entspringt, wo die materiellen Bedingungen ihrer Lösung schon vorhanden oder wenigstens im Prozeß ihres Werdens begriffen sind. In großen Umrissen können asiatische, antike, feudale und modern bürgerliche Produktionsweisen als progressive Epochen der ökonomischen Gesellschaftsformation bezeichnet werden. Die bürgerlichen Produktionsverhältnisse sind die letzte antagonistische Form des gesellschaftlichen Produktionsprozesses, antagonistisch nicht im Sinn von individuellem Antagonismus, sondern eines aus den gesellschaftlichen Lebensbedingungen der Individuen hervorwachsenden Antagonismus, aber die im Schoß der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft sich entwickelnden Produktivkräfte schaffen zugleich die materiellen Bedingungen zur Lösung dieses Antagonismus. Mit dieser Gesellschaftsformation schließt daher die Vorgeschichte der menschlichen Gesellschaft ab.“

()

en | “The general conclusion at which I arrived and which, once reached, became the guiding principle of my studies can be summarised as follows. In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions [not: determines] the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or – this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms – with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure. In studying such transformations it is always necessary to distinguish between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production, which can be determined with the precision of natural science, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophic – in short, ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out. Just as one does not judge an individual by what he thinks about himself, so one cannot judge such a period of transformation by its consciousness, but, on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained from the contradictions of material life, from the conflict existing between the social forces of production and the relations of production. No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed, and new superior relations of production never replace older ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society. Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve, since closer examination will always show that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or at least in the course of formation. In broad outline, the Asiatic, ancient,[A] feudal and modern bourgeois modes of production may be designated as epochs marking progress in the economic development of society. The bourgeois mode of production is the last antagonistic form of the social process of production – antagonistic not in the sense of individual antagonism but of an antagonism that emanates from the individuals' social conditions of existence – but the productive forces developing within bourgeois society create also the material conditions for a solution of this antagonism. The prehistory of human society accordingly closes with this social formation.”

()

fr | « Voici, en peu de mots, le résultat général auquel j'arrivai et qui, une fois obtenu, me servit de fil conducteur dans mes études.

Dans la production sociale de leur existence, les hommes nouent des rapports déterminés, nécessaires, indépendants de leur volonté; ces rapports de production correspondent à un degré donnée du développement de leurs forces productives matérielles. L'ensemble de ces rapports forme la structure économique de la société, la fondation réelle sur laquelle s'élève un édifice juridique et politique, et à quoi répondent des formes déterminées de la conscience sociale. Le mode de production de la vie matérielle domine en général [devrait être: conditionne, non pas détermine] le développement de la vie social, politique et intellectuel. Ce n'est pas la conscience des hommes qui détermine leur existence, c'est au contraire leur existence social qui détermine leur conscience. A un certain degré de leur développement, les forces productives matérielles de la société entre en collision avec les rapport de production existants, ou avec les rapports de propriété au sein desquels elle s'etaient mues jusqu'alors, et qui n'en sontque l'expression juridique. Hier encore forme de développement des forces productives, ces condition se changent en de lourde entraves. Alors commence une ère de révolution sociale. Le changement dans les fondations économiques s'accompagne d'un bouleversement plus ou moins rapide dans tout cet énorme édifice. Quand on considère ces bouleversements, il faut toujours distinguer deux ordres de choses. Il y a le bouleversement matériel des conditions de production économique. On doit le constater dans l'esprit de rigueur des sciences naturelles. Mais il y a aussi les formes juridiques, politiques, religieuses, artistiques, philosophiques, bref les formes idéologiques, dans lesquelles les hommes prennent conscience de ce conflit et le poussent jusqu'au bout. On ne juge pas un individu sur l'idée qu'il a de lui-même. On ne juge pas un époque de révolution d'après la conscience qu'elle a de d'elle même. Cette conscience s'expliquera plutôt par les contrariétés de la vie matérielle, par le conflit qui oppose les forces productives sociales et les rapports de productions. Jamais un société n'expire, avant que soient développées toutes les forces productives qu'elle est assez large pour contenir; jamais des rapports supérieures de production ne se mettent en place, avant que les conditions matérielles de leur existence se soient écloses dans le sein même de la vieille société. C'est pourquoi l'humanité ne se propose jamais que le tâches qu'elle peut remplir : à mieux considérer les choses, on verra toujours que la tâche surgit là où les conditions matérielles de sa réalisation sont déjà formées, ou sont en voie de se créer. Réduits à leurs grandes lignes, les modes de production asiatique, antique, féodal et bourgeois moderne apparaissent comme des époques progressives de la formation économiques de la société. Les rapports de production bourgeois sont la dernière forme antagonique du procès sociale de la production. Il n'est pas question ici d'un antagonisme individuel; nous l'entendons bien plutôt comme le produit des conditions sociales de l'existence des individues; mais les forces productives qui se développent au sein de la société bourgeoise créent dan la même temps les conditions matérielles propre à résoudre cet antagonisme. Avec ce système social c'est donc la pré-histoire de la société humaine qui se clôt. »

(

nl | “Het algemeen resultaat waartoe ik kwam, nadat het eenmaal was verkregen, tot leidraad diende bij mijn studies, kan kort worden samengevat als volgt: In de maatschappelijke produktie van hun leven treden de mensen in bepaalde, noodzakelijke van hun wil onafhankelijke verhoudingen, produktieverhoudingen; deze produktieverhoudingen beantwoorden aan een bepaald ontwikkelingsniveau van hun materiële produktiekrachten. Het geheel van deze produktieverhoudingen vormt de economische struktuur van de maatschappij, de materiële basis waarop zich een juridische en politieke bovenbouw verheft en waaraan specifieke maatschappelijke vormen van bewustzijn beantwoorden. De wijze waarop het materiële leven wordt geproduceerd, is voorwaarde [conditioneert, in tegenstelling tot bepaald] voor het sociale, politieke en geestelijke levensproces in het algemeen. Het is niet het bewustzijn van de mensen dat hun zijn, maar omgekeerd hun maatschappelijk zijn dat hun bewustzijn bepaald. Op een bepaalde trap van hun ontwikkeling raken de materiële produktiekrachten van de maatschappij in tegenspraak met de bestaande produktieverhoudingen, of, wat slechts een juridische uitdrukking voor hetzelfde is, met de eigendomsverhoudingen, waarin zij zich to dusverre hadden bewogen. Van vormen waarin de produktiekrachten tot ontwikkeling kwamen, slaan deze verhoudingen om in ketenen daarvan. Dan breekt een tijdperk van sociale revolutie aan. Met de verandering van de economische grondslag wentelt zich – langzaam of snel – de gehele reusachtige bovenbouw om. Wanneer men dergelijke omwentelingen onderzoekt, moet men altijd onderscheid maken tussen de materiële omwenteling in de economische voorwaarden van de produktie, die natuurwetenschappelijk exact kan worden vastgesteld, en de juridische, politieke, godsdienstige, artitieke of filosofische, kortom ideologische vormen, waarin de mensen zich van dit conflict bewust worden en het uitvechten. Zomin als men een individu beoordeelt naar wat hij van zichzelf vindt, zomin kan men een dergelijk tijdperk van omwenteling beoordelen vanuit zijn eigen bewustzijn; men moet veeleer dit bewustzijn verklaren uit de tegenspraken van het materiële leven, uit het bestaande conflict tussen maatschappelijke produktiekrachten en produktieverhoudingen. Een maatschappijformatie gaat nooit onder, voordat alle produktiekrachten tot ontwikkeling gebracht zijn die zij kan omvatten, en nieuw, hogere produktieverhoudingen treden nooit in de plaats, voordat de materiële bestaansvoorwaarden ervoor in de schoot van de oude maatschappij zelf zijn uitgebroed. Daarom stelt de mensheid zich altijd slechts taken, doe zij kan volbrengen. Want bij nader inzien zal steeds blijken, dat de taak zelf eerst opkomt, wanneer de materiële voorwaarden voor haar volbrenging reeds aanwezig zijn of althans in staat van wording verkeren. In grote trekken kunnen Aziatische, antieke, feodale en modern burgerlijke produktiewijzen aangeduid worden als voortschrijdende tijdperken van de economische maatschappijformatie. De burgerlijke produktieverhoudingen zijn de laatste antagonistische vorm van het maatschappelijke produktieproces: antagonistisch niet in de zin van individueel antagonisme, maar van een antagonisme dat voortkomt uit de maatschappelijke levensvoorwaarden van de individuen. Maar de produktiekrachten die in de schoot van de burgerlijke maatschappij tot ontwikkeling komen, scheppen tegelijk de materiële voorwaarden om dit antagonisme op te lossen. Met deze maatschappijformatie eindigt daarom de voorgeschiedenis van de menselijke maatschappij.”

(

Introduction

de | Wie geht Kapitalismus? Frühe Erklärungsversuche von Turgot, Quesnay, Smith, Say, Ricardo u.a.  (Rätekommunismus, 2023). Also see: Marx, Theorien über den Mehrwert, Ausgabe von Karl Kautsky, 1910. (Rätekommunismus, 2023). Also see: Marx, Theorien über den Mehrwert, Ausgabe von Karl Kautsky, 1910.

“Theories on Capitalist Crises and Imperialism” is a vast subject, of which only a small part (hopefully much to be extended) can be presented here. Basicly (from a proletarian perspective), two thesis have been put forward: one on the saturation of the world market, and the other on the falling rate of profit; both predicting some catastrophic collapse of capitalism.

Although both theories in themselves have proofed to be utterly false, they might lead to a new approach, based on new, further historic experience. Both were partial and also immature responses to real problems posed, a kind of Lamarckian shortcuts. Some general ideas:

- Capitalist crises and imperialism

(we might also discuss “geo-political strategies and tactics”, not to be confused with expansionism (we might also discuss “geo-political strategies and tactics”, not to be confused with expansionism  which is purely territorial), nor, strict, with colonialism which is purely territorial), nor, strict, with colonialism  , can be studied seperately in a limited sense only; in order to get to some understanding of the whole question they need to be integrated into a broader outlook. In the Communist Left, it was held that we can speak of imperialism as a new stage of capitalism when capitalism had conquered the world (despite all massacres and bourgeois brutality in a sense a “progressive” tendency as there remained little room left for “pré-capitalist” production relations; making an end to feudal and pre-feudal societies, and introducing new technology and working methods), and when thus the world could only be “redivided” by the main capitalist powers, bringing very little “progress” any longer, but mainly destruction through rather useless, but also quite unavoidable violent wars of reequilibrying grown inconsistencies; while finally the main capitalist powers confronted each other once again on European soil and all continents; not any longer to expand with French rule capitalism at the expense of feudalism (with all its Napoleonic absurdities), but to impose one national capitalism against equaly capitalist competitors. , can be studied seperately in a limited sense only; in order to get to some understanding of the whole question they need to be integrated into a broader outlook. In the Communist Left, it was held that we can speak of imperialism as a new stage of capitalism when capitalism had conquered the world (despite all massacres and bourgeois brutality in a sense a “progressive” tendency as there remained little room left for “pré-capitalist” production relations; making an end to feudal and pre-feudal societies, and introducing new technology and working methods), and when thus the world could only be “redivided” by the main capitalist powers, bringing very little “progress” any longer, but mainly destruction through rather useless, but also quite unavoidable violent wars of reequilibrying grown inconsistencies; while finally the main capitalist powers confronted each other once again on European soil and all continents; not any longer to expand with French rule capitalism at the expense of feudalism (with all its Napoleonic absurdities), but to impose one national capitalism against equaly capitalist competitors.

- There is no “automatism” in the relation between capitalist crises and proletarian movements; it always is a battle of which the outcome is not assured in advance. There is no economic determinism as “causes” and “effects” are not “one to one” as in simple mechanics; social relations are far more complicated; thus we rather need to discuss them in terms of opportunities seized or missed. When the young Marx talked of “determined” (“bestimmt”), later he rather spoke of “conditioned” (“bedingt”), something very different; a highly “philosophical” dispute, but not without “common sense”; it is, sorry to repeat this, about the difference between simple cause-effect relations and more complex systems

with many variables, and ‘degrees of probability’ rather than certainty. with many variables, and ‘degrees of probability’ rather than certainty.

- Neither can any direct causal relation be demonstrated between capitalist crises and wars: wars might be triggered by economic crises (or other causes), but they are not unavoidable nor inevitable; it rather is a matter of strategic insights (from the limited perspectives of the bourgeoisie) about the subtile differences between strategic and tactical offensive, defensive or neutral policies (which represents, from a more general perspective, very much the same), first theorised by Niccolò Machiavelli

(1469-1527), and, very ambiguous, Carl von Clausewitz (1469-1527), and, very ambiguous, Carl von Clausewitz  (1780-1831), the latter a very “dialectical” thinker, who held that, from a bourgeois perspective, boring periods of peace serve to prepare for the next exciting wars (compare: Si vis pacem, para bellum (1780-1831), the latter a very “dialectical” thinker, who held that, from a bourgeois perspective, boring periods of peace serve to prepare for the next exciting wars (compare: Si vis pacem, para bellum  ). ).

- In between, in the 19th Century there were “Ministries of War”; later, in the 20th Century, “Ministries of War and Peace”; and finally “Ministries of Defense”. For a more proletarian perspective one might want to refer to Proletarian internationalism.

- As for political economy, we need to distinguish between puntual, cyclical and structural crises.

- Punctual crises follow from the proces of production of capital (Volume I of Marx’ Capital), caused by non-economic factors, as for instance natural disasters, sudden shortages of raw materials, machinery or labor; in general hazardous and limited in scope and extend; yet natural disasters and pandemics might have worldwide consequences, even disrupting cyclical and structural crises, and are evermore caused or accelarated by capitalist production, distribution and consumption.

- Cyclical crisis follow from the proces of circulation of capital (Volume II of Marx’ Capital), they occur every 7-12 years and always start in the financial sector; it is a pendulum going from new investments with high profit rates to over-investment ending in low profit rates because of high competition (it is about the bipolar disorder of ‘investors’); improductive capital, which continues production despite not making profits, in order to at least win back (in money) a part of constant capital (buildings, machinerie, stocks, …) holds down prices and lengthens the outcome before a new cycle can start; thus they are solved by the gradual or active destruction of improductive capital (which is why Marx spoke about the moral depreviation of capital before physical wear and tear occures), wars too can play a role by the destruction of the whether or not obsolete competing industries.

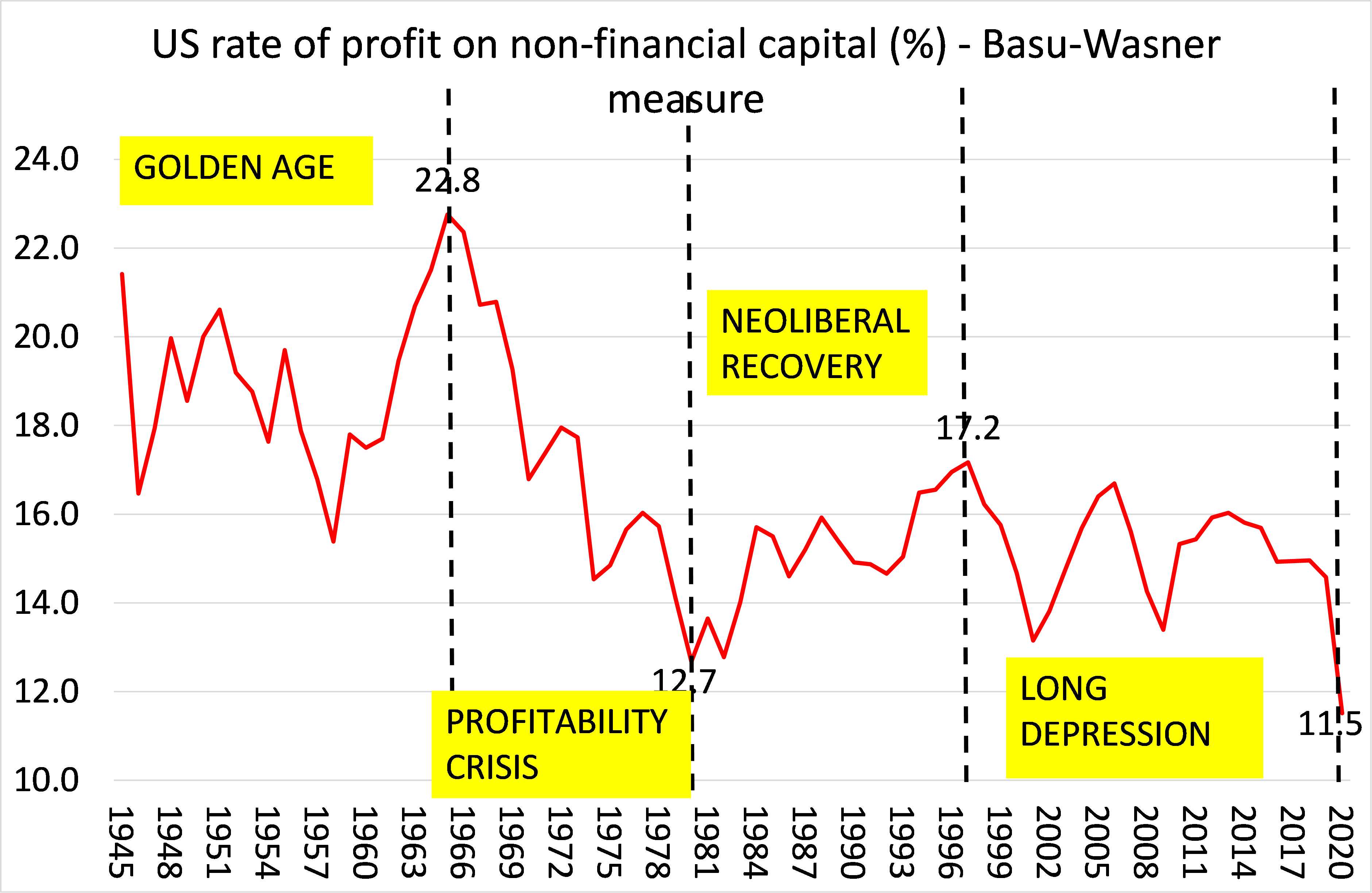

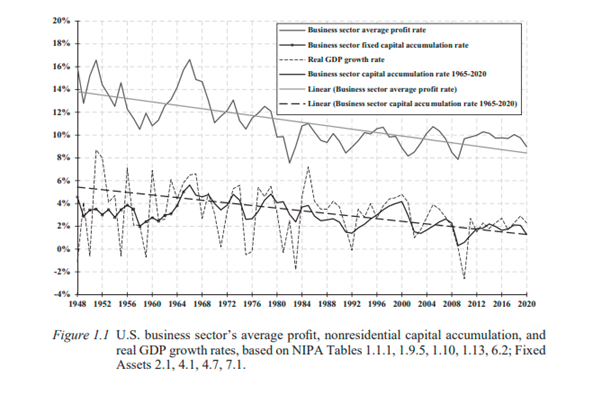

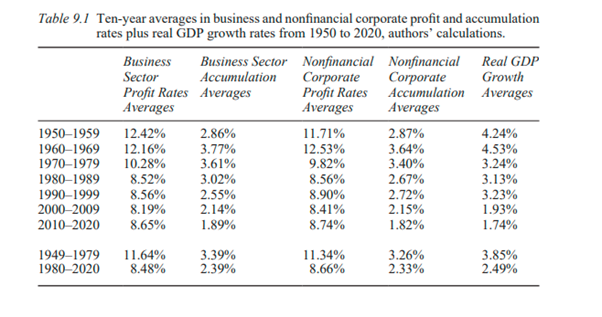

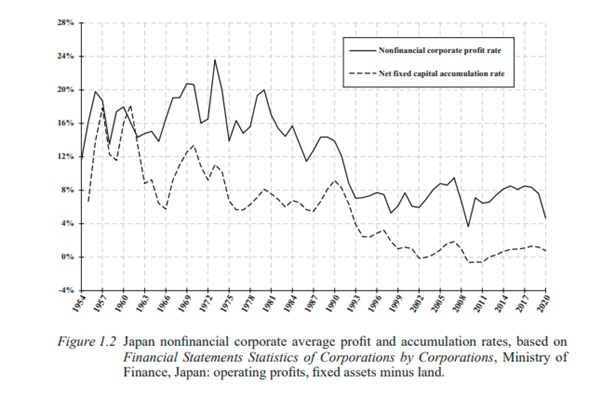

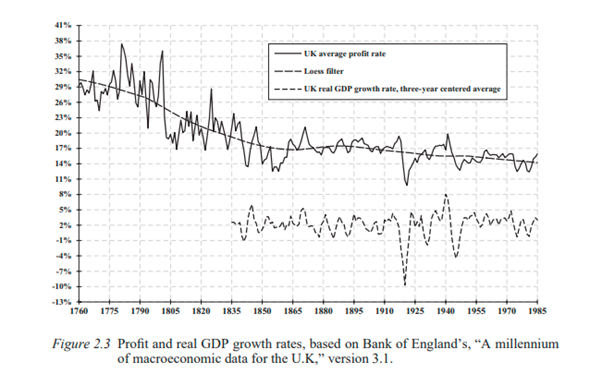

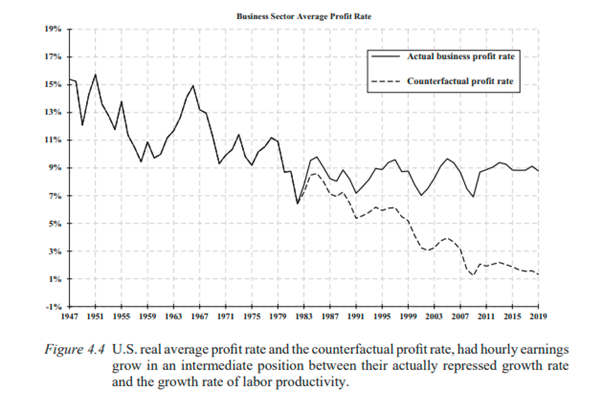

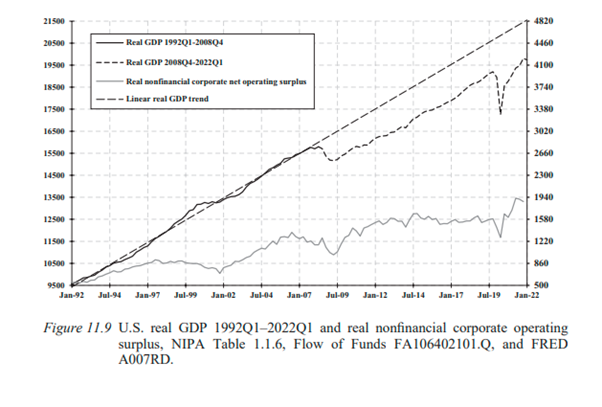

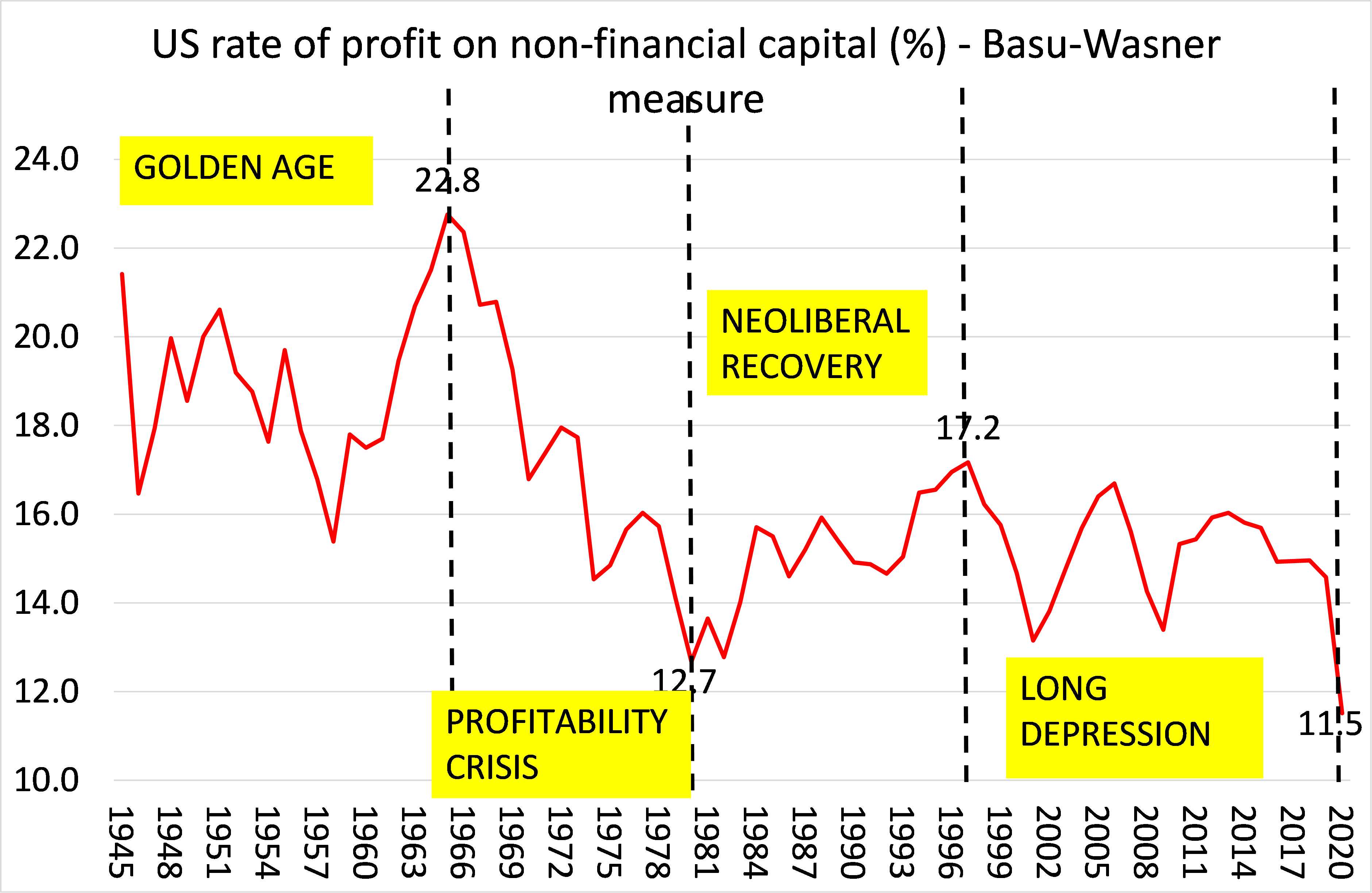

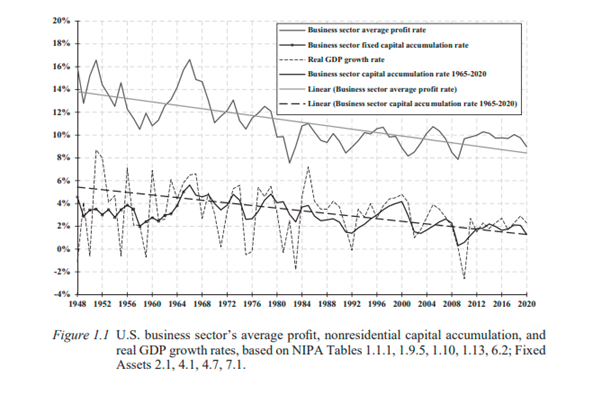

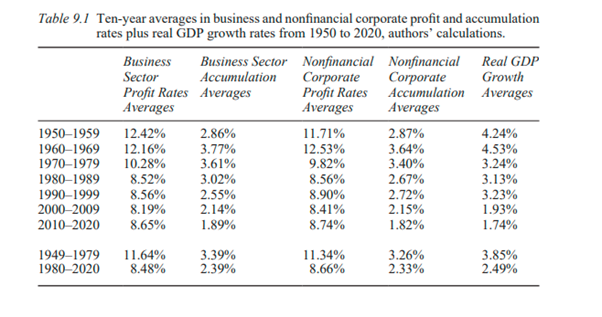

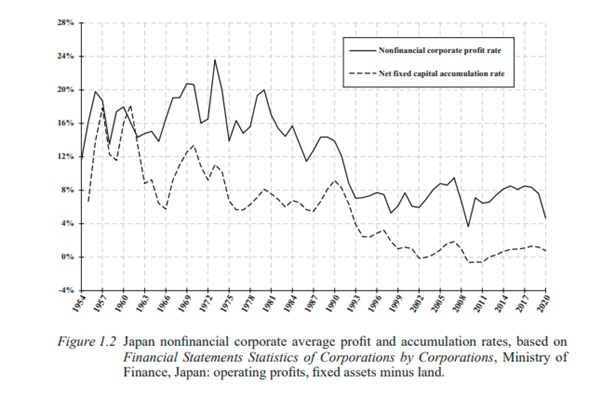

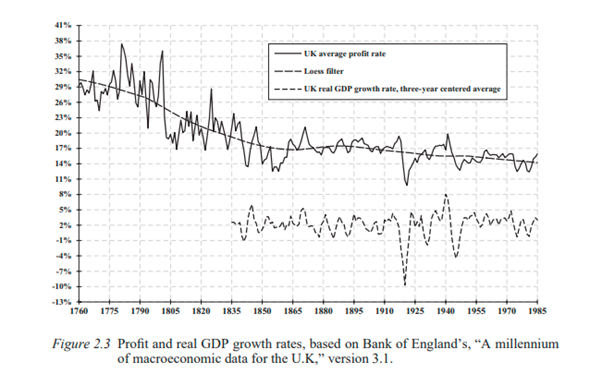

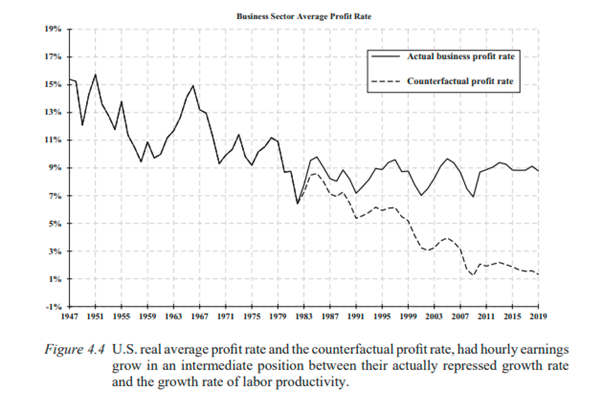

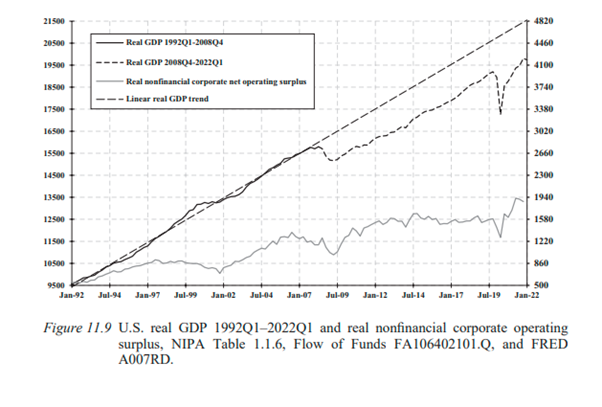

- Structural crises follow from the capitalist proces as a whole (Volume III of Marx’ Capital); they can be detected only as a tendency in the longer turn (or even only over the whole history of capitalism), and follow from the general “law” of the average profitrate to fall (which does not apply to cyclical crises having other causes for the fall of the profitrate; yet the two can coincide); they last much longer than cyclical crises (a structural crisis might contains several cyclical crises), and tend to widen and deepen, and also to extend in time, but the bourgeoisie can also anticipate them; they are ‘solved’ by the preparation for generalised war, as from 1912 and 1933 onwards, with a probability of repetition today of the militarisation of the whole of society, if not stopped by popular movements in which the working class (today first of all the huge sectors of education and health, far less industry) takes the lead. One structural crisis started in 1873 (stagnation rather than “negative growth”, the period was called La Belle Époque

; as investments had little returns, a lot of money was spent on luxery, including fancy buildings and impressionist paintings), the next started in 1929 (a real collapse, ending with the reconstruction after the Second World War), then one (less evident) starting in 1966 (with the beginning of “stagflation”), and the following in 1996, 2001 or 2007, all of this can be disputed as in this period the distinction between what is structural, cyclical or punctual becomes difficult to make. ; as investments had little returns, a lot of money was spent on luxery, including fancy buildings and impressionist paintings), the next started in 1929 (a real collapse, ending with the reconstruction after the Second World War), then one (less evident) starting in 1966 (with the beginning of “stagflation”), and the following in 1996, 2001 or 2007, all of this can be disputed as in this period the distinction between what is structural, cyclical or punctual becomes difficult to make.

- There is, by consequence, a tendency of ever wider, deeper and longer structural crises (ever more a sign of demice), and within that process, relatively less important, yet still very destructive cyclical crises (once most of all emergence crises, then moreover crises of decline) (1), and then evermore frequent punctual crises on top of it (natural catastrophes caused mostly by capitalist activity, wars, social upheavals and also ‘spiritual’ disarray).

- It is a larger than Marxian axiom that in capitalism new productive investment drives ‘economic growth’, but only on the condition that some ‘effective demand’ might be expected, an expectation which might be ‘irrational’. The growth of the capitalist economy, however, depends not on ‘effective demand’ (i.e. ‘purchasing power’, Keynes

, cynically ignoring all the needs which cannot be satisfied because of lack of money), ‘money supply’ (Austrian school , cynically ignoring all the needs which cannot be satisfied because of lack of money), ‘money supply’ (Austrian school  ) or ‘interest rates’ (Monetarism" ) or ‘interest rates’ (Monetarism"  and the Chicago School and the Chicago School  ), but on profitability; the higher it is (real or just expected, thus very ‘psychological’), the more new investment is being made; the lower it is, the more the bourgeoisie also tends to spend the lower return on its own luxury instead of investing it (thus becomimng a parasite) (2). The Keynesian solution to the crisis, creating artificial ‘effective demand’ by excessive state-spending financed by the ‘creation of money’ through licenses to print money (excessively made use of in Germany and Russia in the 1920s (before Keynes), leading to galloping inflation, at the expense of ‘savers’ and in favour of debters, like the states themselves), had some short-term effect, and came to an end in the 1970s as inflation rose without reducing stagnation any longer, ending in ‘stagflation’. The following neo-liberal politics of cheap money supply (a short-term compensation for low profitability) through state banks; initially successful in the short turn to stimulate artificial investment with little return, wore out in the beginning of the 21rst Century due to spiraling debts from the 1980s onward, ending in national bankruptcies, in which the i.m.f. and the World Bank had to interfer. Today bourgeois-economists have to admit that their ‘models’ were wrong (like Alan Greenspan ), but on profitability; the higher it is (real or just expected, thus very ‘psychological’), the more new investment is being made; the lower it is, the more the bourgeoisie also tends to spend the lower return on its own luxury instead of investing it (thus becomimng a parasite) (2). The Keynesian solution to the crisis, creating artificial ‘effective demand’ by excessive state-spending financed by the ‘creation of money’ through licenses to print money (excessively made use of in Germany and Russia in the 1920s (before Keynes), leading to galloping inflation, at the expense of ‘savers’ and in favour of debters, like the states themselves), had some short-term effect, and came to an end in the 1970s as inflation rose without reducing stagnation any longer, ending in ‘stagflation’. The following neo-liberal politics of cheap money supply (a short-term compensation for low profitability) through state banks; initially successful in the short turn to stimulate artificial investment with little return, wore out in the beginning of the 21rst Century due to spiraling debts from the 1980s onward, ending in national bankruptcies, in which the i.m.f. and the World Bank had to interfer. Today bourgeois-economists have to admit that their ‘models’ were wrong (like Alan Greenspan  ), and, however hard they are trying, there is nothing new to propose. Now a combination of these policies is tried, and it will fail in terms. New inflation will make an end to cheap money supply, and the states are not capable any longer to create artificial ‘effective demand’ as it raises state-debts to new heights, preventing new investments, ending in the bankruptcies of whole states. New state-debts are financed by inflation plus cheap artificial money for speculative investments, and the two don’t go well together. Today, the imagination of some bourgeois-intellectuals goes no further than Helicopter money ), and, however hard they are trying, there is nothing new to propose. Now a combination of these policies is tried, and it will fail in terms. New inflation will make an end to cheap money supply, and the states are not capable any longer to create artificial ‘effective demand’ as it raises state-debts to new heights, preventing new investments, ending in the bankruptcies of whole states. New state-debts are financed by inflation plus cheap artificial money for speculative investments, and the two don’t go well together. Today, the imagination of some bourgeois-intellectuals goes no further than Helicopter money  . It ends up in ever greater local and also global breakdowns which are ever harder to repair and in wars started by the weakest, or rather well hidden by the strongest in ‘preventive anticipation’ (by means of hidden strangulation). . It ends up in ever greater local and also global breakdowns which are ever harder to repair and in wars started by the weakest, or rather well hidden by the strongest in ‘preventive anticipation’ (by means of hidden strangulation).

- Capitalism in crises poses a double problem: a surplus of capital which cannot be invested profitably; and by consequence there also remains a surplus of labor-power which cannot be exploited any longer, thus lower wages and less spending. One might try to force the two, capital and labor, together: unprofitable investments (financed by taxes, confiscations, or whatever) and the ‘creation of jobs’ (useful or not); but the real way out has proved to be war, another redivision of the world, which hasn’t solved anything for the better for more than a century and a half or longer. Capitalism became obsolete when the world, in its great outlines, was conquered by capitalism in the beginning of the 20th Century, with subsequent endless wars of redivision.

- The slave-trade wasn’t all that profitable; it rather was a kind of Russian Roulette: you could double your capital or lose all (one out of three boats didn’t return); by contrast, the exploitation of slaves paved the way for huge capitals which, from a certain level of development, could very well do without slavery, even more, for which slavery finally became a counterweight, which is why it was abolished, certainly not for humanitarian reasons. The great British liberal writer John Locke

lost all as he was just a short-turn adventurer. lost all as he was just a short-turn adventurer.

- Colonial investment (mostly mining and plantations, thus looting and plundering nature as well as the work force) gave a more stable revenue. Untill the 1850s, the purely parasitic colonial class was still dominant, with plantations and mining all over the world. The profits were hardly re-invested, the bourgeoisie rather lived by it. The proletariat in the centres of capitalism consisted, by consequence, in majority still of domestic workers (cq. household staff), rural workers (and miners). Thus quantitatively agriculture (in numbers of workers involved and capital invested) still dominated over industry; and when industry took over agriculture started to follow industrial methods, with severe consequences.

- Finally, the question of the reproduction of labor-force was posed: when labor is not any longer provided “by nature” it needs to be reproduced on capitalist conditions, including schooling, housing, health-care, pensions and whatever more, which gets ever more difficult. Everything nature does not provide anymore, or not enough, needs to be produced or reproduced. In capitalism the looting and plundering of nature, the work force and the human mind are the norm until these resources start to fail. Then they need to be reproduced until it becomes ever more difficult and ends in stagnation and decline, ending in ever greater wars to take hold of the remaining sources and the technology to reproduce them; including the strategic territorial positions. A part of this quite simple question is known as the problem of the ‘formal’ as against ‘reel’ domination of the working class, a question in its great outlines already settled a long time before the First World War.

es |  ¿Derrumbe del capitalismo o sujeto revolucionario? / [Giacomo Marramao], Paul Mattick, Anton Pannekoek, Karl Korsch. – Mexico : Ediciónes Pasado y Presente. – 149 p. –(Cuadernos de Pasado y Presente ; 78) ¿Derrumbe del capitalismo o sujeto revolucionario? / [Giacomo Marramao], Paul Mattick, Anton Pannekoek, Karl Korsch. – Mexico : Ediciónes Pasado y Presente. – 149 p. –(Cuadernos de Pasado y Presente ; 78)

- Teoría del derrumbe y capitalismo organizado en las discusiones del “extremismo histórico” / Giacomo Marramao 7

- ¿Derrumbe del capitalismo o sujeto revolucionario? 51

- Prólogo . Paul Mattick 53

- La teoría de derrumbe del capitalismo / Anton Pannekoek 62

- Objetivo / Paul Mattick 85

- Sobre la teoría marxiana de la acumulación y del derrumbe / Paul Mattick 86

- Fundamentos de una teoría revolucionaria de las crisis / Karl Korsch 107

- Algunos supuestos básicos para una discusión materialista de la teoría de las crisis / Karl Korsch 124

- La crisis mortal del capitalismo / Paul Mattick 132

Some restrictive and technical Wikipedia articles with a lot of references in the German and also Armenian lemmas:

ar | نظرية الأزمات

de | Marxistische Krisentheorie

dk | Kriseteori

en | Crisis theory

es | Crisis cíclicas

hy | Ճգնաժամային տեսություն

pt | Crise do capitalismo

The demystification of “value”

As there is a new mystification of “value” (notably by the “communisators” (3)) it is necessary to return to some basic concepts.

Marx’ first scientific publication (beyond previous polemics and political statements), Zur Kritik der politischen Ökonomie  was published in German in 1859. In other languages often a century or more later, or never; in English as late as 1970 (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy was published in German in 1859. In other languages often a century or more later, or never; in English as late as 1970 (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy  ). The year 1859 ). The year 1859  was of some importance. Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published that year; the London sewage system was constructed, the British liberal party founded while the chimes of Big Ben rang for the first time over London. was of some importance. Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published that year; the London sewage system was constructed, the British liberal party founded while the chimes of Big Ben rang for the first time over London.

Marx held this to be the scientific basis (very little studied), whilst in Capital (Part I, Commodities and money) it was popularized, though with some further additions (4).

The point of departure of the “classical” political economy (Adam Smith  , David Ricardo , David Ricardo  and Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi and Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi  , not to name all the others; the idea is much older) was the labor theory of value , not to name all the others; the idea is much older) was the labor theory of value  (Marx called it a “concept” rather than a “theory” (“Wertbegriff”)): the “value” of a commodity is conditioned (not determined) by the “average socially necessary labor” to produce it. Marx’ Capital, by the way, does not contain a ‘theory’ (which can be verified or falsified), but is to be understood as a ‘theoretical model of a complex system’ (which proves itself by making correct predictions, see further on). (Marx called it a “concept” rather than a “theory” (“Wertbegriff”)): the “value” of a commodity is conditioned (not determined) by the “average socially necessary labor” to produce it. Marx’ Capital, by the way, does not contain a ‘theory’ (which can be verified or falsified), but is to be understood as a ‘theoretical model of a complex system’ (which proves itself by making correct predictions, see further on).

Marx got beyond the “classics” in 1859 by not starting from some abstract “value” (a false generalisation he finally broke up) but from “the commodity”, and then making a distinction between “use value” and “exchange value”, which avoided at bit the false impression that these two “categories” would be specific forms of some abstract general “category” called “value” (a confused obsession of the “classics”, leading to contradictions). The two are very different phenomena, not related to each other any other than that an exchange value must be useful, or, rather, be salable as such (including the pious sermons of the priests). Yet the term “use value” remained confusing; one might also speak of “goods” which might be “useful” or not, independant of the question of them having “value” (everything found in nature is for free, but when it gets scarce and needs to be produced – implying labor – there might be a “price” to it; but fortunately there are also nice people who render services for free). Use-values, until now, have no general equivalent and cannot be quantified (mesured) other than in tons of steels or gallons of milk (5).

One might note that it was never formulated as a “law” of labor value (such a “law” is nowhere to be found), although it was often presented as such. The “labor theory of value” (beyond a mere idea already developped in the 12th Century and even before) is in fact a “theoretical assumption”; a point of departure (6).

In the 18th Century it was openly stated to be a class position, not of the proletariat, but of the emergent (the third estate of commoners and early bourgeois, not yet massively exploiting those who had nothing) class of “independant arts and crafts”, as against the feudal position that only nature provided wealth, which corresponded to a period in which most economic transactions were “in nature”, without much money implied and in which feudal “ranks” with territorial souvereinty (which is opposed to landed property) required their part of what nature produced.

In fact, the transformation of territorial souvereinty (“noblesse oblige”; “there is no land without a master”) into landed property is one of the biggest scandals of the “primitive accumulation” of capital (7), and it must be said that Karl Marx wasn´t very much aware of it, at least not in the very little which was published of his notes on the question.

The “labor theory of value” was not much appreciated any longer by the bourgeoisie with the rise in importance of modern wage-laborers (8).

Around this a whole abstract academic debate might evolve around paradigms  according to Thomas Kuhn according to Thomas Kuhn  or his critic Imre Lakatos or his critic Imre Lakatos  , both hiding however the class nature of the opponents. , both hiding however the class nature of the opponents.

Some years after 1859, quite shamefully and cowardly (9), without any formal refutation this reasonable and also logic point of departure, was silently and dishonestly abandoned and without any argumentation replaced by a very unreasonable and mere psychological marginal utility  . Ever since, bourgeois economics has remainded a pseudo-scientific psychological ideology, i.e. the subjective theory of value . Ever since, bourgeois economics has remainded a pseudo-scientific psychological ideology, i.e. the subjective theory of value  (10) which tries to impress and astonish with very fancy mathematics (11). (10) which tries to impress and astonish with very fancy mathematics (11).

First by William Stanley Jevons  , a mystic mathematician (British, 1863, thus after Marx’ Zur Kritik (1959), but before Marx’ Capital (1867)), then by Carl Menger , a mystic mathematician (British, 1863, thus after Marx’ Zur Kritik (1959), but before Marx’ Capital (1867)), then by Carl Menger  (Austrian, 1871, he started studying the question in the year that Marx’ Capital was published), and finally by Marie-Esprit-Léon Walras (Austrian, 1871, he started studying the question in the year that Marx’ Capital was published), and finally by Marie-Esprit-Léon Walras  (French, 1874, after the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune of Paris). Neither of these three heroes referred to the works by Karl Marx, although all three must have studied Zur Kritik and the first volume of Capital. They could have criticised those; they could even have tried to make an end to the whole “concept of value”; yet they refrained because they couldn’t (12). The subjective theory of value (it only is a marginal theory of price which fluctuates around value) was further mathemathically expanded and popularized by Alfred Marshall (French, 1874, after the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune of Paris). Neither of these three heroes referred to the works by Karl Marx, although all three must have studied Zur Kritik and the first volume of Capital. They could have criticised those; they could even have tried to make an end to the whole “concept of value”; yet they refrained because they couldn’t (12). The subjective theory of value (it only is a marginal theory of price which fluctuates around value) was further mathemathically expanded and popularized by Alfred Marshall  (British, 1842-1924, published Principles of Economics in 1890; hardly studied by the marxists of the time, something to be further investigated), resulting in the law of supply and demand (British, 1842-1924, published Principles of Economics in 1890; hardly studied by the marxists of the time, something to be further investigated), resulting in the law of supply and demand  , which admittedly explains a modification of the price, yet does not change the value in any way, and Marx was not unaware of this very simple phenomenon, as he referred to the Shakespearean “A horse, a horse, my Kingdom for a Horse” (13). , which admittedly explains a modification of the price, yet does not change the value in any way, and Marx was not unaware of this very simple phenomenon, as he referred to the Shakespearean “A horse, a horse, my Kingdom for a Horse” (13).

It provoked much later a very “philosophical” chaos around the question whether or not such “point of departure” needed “proof”; it is, however, a matter of historical class perspective.

Well, there was not even the least “scientific foundation” for the quite psychological concept of “marginal utility  ” (it represents nothing more than a short-sighted bourgeois vision); although the argument about the “theoretical assumption” was turned with force against Karl Marx, implying the whole of “classical political economy” (which he had already abolished) behind him. In a letter of 1868 to Ludwig Kugelmann Karl Marx adressed the question as follows: ” (it represents nothing more than a short-sighted bourgeois vision); although the argument about the “theoretical assumption” was turned with force against Karl Marx, implying the whole of “classical political economy” (which he had already abolished) behind him. In a letter of 1868 to Ludwig Kugelmann Karl Marx adressed the question as follows:

de | „Das Geschwätz über die Notwendigkeit, den Wertbegriff zu beweisen, beruht nur auf vollständigster Unwissenheit, sowohl über die Sache, um die es sich handelt, als die Methode der Wissenschaft. Daß jede Nation verrecken würde, die, ich will nicht sagen für ein Jahr, sondern für ein paar Wochen die Arbeit einstellte, weiß jedes Kind. Ebenso weiß es, daß die den verschiednen Bedürfnismassen entsprechenden Massen von Produkten verschiedne und quantitativ bestimmte Massen der gesellschaftlichen Gesamtarbeit erheischen. Daß diese Notwendigkeit der Verteilung der gesellschaftlichen Arbeit in bestimmten Proportionen durchaus nicht durch die bestimmte Form der gesellschaftlichen Produktion aufgehoben, sondern nur ihre Erscheinungsweise ändern kann, ist self-evident [selbstverständlich]. Naturgesetze können überhaupt nicht aufgehoben werden. Was sich in historisch verschiednen Zuständen ändern kann, ist nur die Form, worin jene Gesetze sich durchsetzen. Und die Form, worin sich diese proportioneile Verteilung der Arbeit durchsetzt in einem Gesellschaftszustand, worin der Zusammenhang der gesellschaftlichen Arbeit sich als Privataustausch der individuellen Arbeitsprodukte geltend macht, ist eben der Tauschwert dieser Produkte.

Die Wissenschaft besteht eben darin, zu entwickeln, wie das Wertgesetz sich durchsetzt. Wollte man also von vornherein alle dem Gesetz scheinbar widersprechenden Phänomene „erklären“, so müßte man die Wissenschaft vor der Wissenschaft liefern. Es ist grade der Fehler Ricardos, daß er in seinem ersten Kapitel über den Wert alle möglichen Kategorien, die erst entwickelt werden sollen, als gegeben voraussetzt, um ihr Adäquatsein mit dem Wertgesetz nachzuweisen.

Allerdings beweist andrerseits, wie Sie richtig unterstellt haben, die Geschichte der Theorie, daß die Auffassung des Wertverhältnisses stets dieselbe war, klarer oder unklarer, mit Illusionen verbrämter oder wissenschaftlich bestimmter. Da der Denkprozeß selbst aus den Verhältnissen herauswächst, selbst ein Naturprozeß ist, so kann das wirklich begreifende Denken immer nur dasselbe sein, und nur graduell, nach der Reife der Entwicklung, also auch des Organs, womit gedacht wird, sich unterscheiden. Alles andre ist Faselei.

Der Vulgärökonom hat nicht die geringste Ahnung davon, daß die wirklichen, täglichen Austauschverhältnisse und die Wertgrößen nicht unmittelbar identisch sein können. Der Witz der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft besteht ja eben darin, daß a priori keine bewußte gesellschaftliche Reglung der Produktion stattfindet. Das Vernünftige und Naturnotwendige setzt sich nur als blindwirkender Durchschnitt durch. Und dann glaubt der Vulgäre eine große Entdeckung zu machen, wenn er der Enthüllung des inneren Zusammenhangs gegenüber drauf pocht, daß die Sachen in der Erscheinung anders aussehn. In der Tat, er pocht drauf, daß er an dem Schein festhält und ihn als Letztes nimmt. Wozu dann überhaupt eine Wissenschaft?

Aber die Sache hat hier noch einen andren Hintergrund. Mit der Einsicht in den Zusammenhang stürzt, vor dem praktischen Zusammensturz, aller theoretische Glauben in die permanente Notwendigkeit der bestehenden Zustände. Es ist also hier absolutes Interesse der herrschenden Klassen, die gedankenlose Konfusion zu verewigen. Und wozu anders werden die sykophantischen Schwätzer bezahlt, die keinen andern wissenschaftlichen Trumpf auszuspielen wissen, als daß man in der politischen Ökonomie überhaupt nicht denken darf!

Jedoch satis superque [genug und ubergenüg]. Jedenfalls zeigt es, wie sehr diese Pfaffen der Bourgeoisie verkommen sind, daß Arbeiter und selbst Fabrikanten und Kaufleute mein Buch verstanden und sich darin zurechtgefunden haben, während diese „Schriftgelehrten(!)“ klagen, daß ich ihrem Verstand gar Ungebührliches zumute.“

(Karl Marx an Ludwig Kugelmann, 11. Juli 1868, m.e.w., Bd. 32, S. 552-554.)

en | “The chatter about the need to prove the concept of value arises only from complete ignorance both of the subject under discussion and of the method of science. Every child knows that any nation that stopped working, not for a year, but let us say, just for a few weeks, would perish. And every child knows, too, that the amounts of products corresponding to the differing amounts of needs demand differing and quantitatively determined amounts of society’s aggregate labor. It is self-evident that this necessity of the distribution of social labor in specific proportions is certainly not abolished by the specific form of social production; it can only change its form of manifestation. Natural laws cannot be abolished at all. The only thing that can change, under historically differing conditions, is the form in which those laws assert themselves. And the form in which this proportional distribution of labor asserts itself in a state of society in which the interconnection of social labor expresses itself as the private exchange of the individual products of labor, is precisely the exchange value of these products.

Where science comes in is to show how the law of value asserts itself. So, if one wanted to ‘explain’ from the outset all phenomena that apparently contradict the law, one would have to provide the science before the science. It is precisely Ricardo’s mistake that in his first chapter, on value, (*) all sorts of categories that still have to be arrived at are assumed as given, in order to prove their harmony with the law of value.

On the other hand, as you correctly believe, the history of the theory of course demonstrates that the understanding of the value relation has always been the same, clearer or less clear, hedged with illusions or scientifically more precise. Since the reasoning process itself arises from the existing conditions and is itself a natural process, really comprehending thinking can always only be the same, and can vary only gradually, in accordance with the maturity of development, hence also the maturity of the organ that does the thinking. Anything else is drivel.

The vulgar economist has not the slightest idea that the actual, everyday exchange relations and the value magnitudes cannot be directly identical. The point of bourgeois society is precisely that, a priori, no conscious social regulation of production takes place. What is reasonable and necessary by nature asserts itself only as a blindly operating average. The vulgar economist thinks he has made a great discovery when, faced with the disclosure of the intrinsic interconnection, he insists that things look different in appearance. In fact, he prides himself in his clinging to appearances and believing them to be the ultimate. Why then have science at all?

But there is also something else behind it. Once interconnection has been revealed, all theoretical belief in the perpetual necessity of the existing conditions collapses, even before the collapse takes place in practice. Here, therefore, it is completely in the interests of the ruling classes to perpetuate the unthinking confusion. And for what other reason are the sycophantic babblers paid who have no other scientific trump to play except that, in political economy, one may not think at all!

But satis superque. (**) In any case, it shows the depth of degradation reached by these priests of the bourgeoisie: while workers and even manufacturers and merchants have understood my book and made sense of it, these ‘learned scribes’ (!) complain that I make excessive demands on their comprehension.”

(Letter of Karl Marx to Ludwig Kugelmann, 11 July 1868, m.e.c.w., Vol. 43, p. 68-69.)

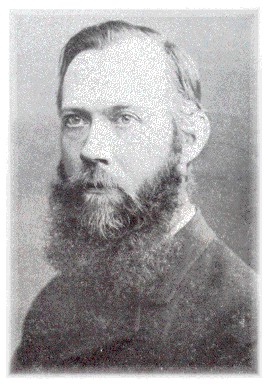

Karl Kautsky

Mostly neglected, Karl Kautsky  (Wikipedia, also see the other languages) was the main theoretician until 1909, and his works are quite unrightfully ignored. (Wikipedia, also see the other languages) was the main theoretician until 1909, and his works are quite unrightfully ignored.

Marxists’ Internet Archive, well represented in German and English (although a lot remains missing), poorly in most other languages: de  | en | en  | es | es  | fr | fr  | it | it  | nl | nl  . .

A lot can be found here: Internet Archive  . .

Notably (to be completed):

- De economische theorieën van Karl Marx

: Populair uiteengezet en toegelicht door Karl Kautsky (vertaald uit het Duitsch door J.F. Ankersmit). – Amsterdam : S.L. van Looy, 1900. – 158 p.. : Populair uiteengezet en toegelicht door Karl Kautsky (vertaald uit het Duitsch door J.F. Ankersmit). – Amsterdam : S.L. van Looy, 1900. – 158 p..

-

. .

-

. .

-

. .

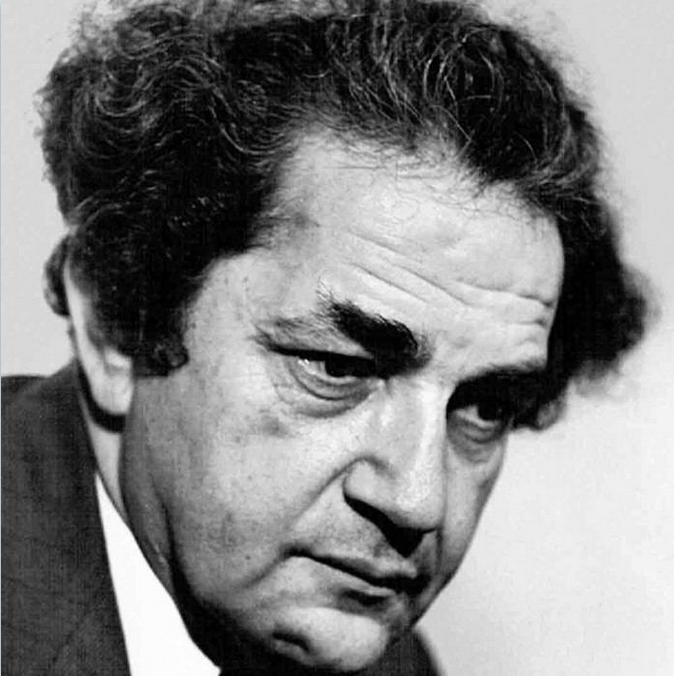

Rudolf Hilferding

Though not implied in the Communist Left, quite important was Rudolf Hilferding, of the “Austrian School of Marxism” (not to be confused with the Austrian School of Liberalism  ) initially quite close to the “Dutch School of Marxism”, but then there were second thoughts; he is well represented in Wikipedia:

de ) initially quite close to the “Dutch School of Marxism”, but then there were second thoughts; he is well represented in Wikipedia:

de  |

en |

en  |

es |

es  |

fr |

fr  |

nl |

nl  ;

by contrast, he is poorly represented in the Marxists’ Internet Archive: de ;

by contrast, he is poorly represented in the Marxists’ Internet Archive: de  |

en |

en  |

fr |

fr  . .

de |  Das Finanzkapital : Eine Studie über die jüngste Entwicklung des Kapitalismus / Rudolf Hilferding; Mit einem Vorwort von Fred Oelßner. – Berlin : Dietz Verlag, 1955.&nsp;– 564 S. Das Finanzkapital : Eine Studie über die jüngste Entwicklung des Kapitalismus / Rudolf Hilferding; Mit einem Vorwort von Fred Oelßner. – Berlin : Dietz Verlag, 1955.&nsp;– 564 S.

en |  Finance capital : A study of the latest phase of capitalist development / Rudolf Hilferding; Edited with an Introduction by Tom Bottomore; From Translations by Morris Watnick and Sam Gordon. – London : Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1981. – 466 p. Finance capital : A study of the latest phase of capitalist development / Rudolf Hilferding; Edited with an Introduction by Tom Bottomore; From Translations by Morris Watnick and Sam Gordon. – London : Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1981. – 466 p.

es |  El Capital Financiero / Rudolf Hilferding; Traducción de V. Romano Garcia. – Madrid : Tecnos, S.A., 1963. – 420 p. El Capital Financiero / Rudolf Hilferding; Traducción de V. Romano Garcia. – Madrid : Tecnos, S.A., 1963. – 420 p.

Quelle: Internet Archive

Parvus

Die Handelskrisis und die Gewerkschafte : Nebst Anhang: Gesetzentwurf über den achtstündigen Normalarbeitstag / Parvus. – München : Verlag M. Ernst, 1901. – 64 S. Die Handelskrisis und die Gewerkschafte : Nebst Anhang: Gesetzentwurf über den achtstündigen Normalarbeitstag / Parvus. – München : Verlag M. Ernst, 1901. – 64 S.

Quelle: Internet Archive  (Ursprünglich Bayerische Staatsbibliothek) (Ursprünglich Bayerische Staatsbibliothek)

Rosa Luxemburg

Although Rosa Luxemburg launched a theoretical flawed thesis (capitalism would not be able to survive without opening up ever new extra-capitalist markets as the realisation of surplus-value would not be possible without sales beyond the bounderies of existing capitalism) (14); she did have a very serious argument about the restrictions given by the constitution of the world-market (15). Other than she thougt, cyclical capitalist recessions are not caused by the saturation of markets; the saturation is a consequence of failing new investments (investments define “demand” in the middle turn; yet people without “purchasing power” might revolt).

However, the extra-economic fact that the world is round does give a limit to capitalist expansion, about which the later Anton Pannekoek, without however refering back to Rosa Luxemburg, after having criticised her, wrote:

“But the earth is a globe, of limited extent. The discovery of its finite size accompanied the rise of capitalism four centuries ago, the realization of its finite size now marks the end of capitalism.”

(The Workers’ Councils, see further on).

If the world would have been flat and infinite in all directions (the argument seriously surfaced in France, 1968), there would have been some more room, but when the centres would start to lose profitability the extension could not compensate for it in the long run. On the other hand, the world population keeps growing (since the beginning of capitalism even exponentially), which also expands the market, even when not territorially. And finally, with the development of productive forces the needs increase, also expanding the market on the condition that they are translated into some ‘effective demand’ of the exploited which need to be ever more qualified, as otherwise they are replaced by robots.

This also gives way to a whole very nice discussion about the growing mass of profits compensating for the falling rate of profit, which doesn’t work in the long run neither, and in the short run only for bigger capitals.

Great markets on the Moon and Mars (which has also been put forward as a solution, also in France, 1968) cannot be expected neither in the centuries to come; so there is a serious problem; though somewhat different, and moreover more complicated than Rosa Luxemburg anticipated (16).

Once the earth was divided between capitalist nations towards the end of the 19th Century (firing power was much more decisive than trade, although low prices are certainly compelling arguments) a serieus problem occured. And when the bourgeoisie arises, the most profit-promising enterprises are exploited first, thus the rest is already somewhat less promising.

But then new things might come up, like crude oil, or whatever new energy-sources (fusion power  would solve a lot of problems, but not the problems of capitalism), as the disposition of electricity becomes quite decisive, and also rending everything ever more vulnerable. would solve a lot of problems, but not the problems of capitalism), as the disposition of electricity becomes quite decisive, and also rending everything ever more vulnerable.

In the absence of international law – which, by definition, is the law of the strongest, of course including the “rights of nations to self-determination”, “human rights” and “democracy” elsewhere, as formulated by the “democrat” and “internationalist” Woodrow Wilson  (mostly turned against the own allied colonial European competitors and some others as well) – and, subsequently, by Lenin (with catastrophic consequences in the Caucasus and elsewhere, and certainly in Eastern Asia), one might be interested in the view of Anton Pannekoek on the matter – as very expensive merchandises to be exported, however not even respected at home – it can only be redivided through wars; bringing ever less expansion of capitalism, and ever more destruction. (mostly turned against the own allied colonial European competitors and some others as well) – and, subsequently, by Lenin (with catastrophic consequences in the Caucasus and elsewhere, and certainly in Eastern Asia), one might be interested in the view of Anton Pannekoek on the matter – as very expensive merchandises to be exported, however not even respected at home – it can only be redivided through wars; bringing ever less expansion of capitalism, and ever more destruction.

Yet two further distinctions need to be made:

- When the world market is territorially divided between capitalist enterprises and nations, this does not imply by any means that the whole of the world population is integrated into bourgeois society through generalised wage labor; in fact, the great majority is not; and an ever greater part of the world population is excluded or marginalised; their original livelihoods have disappeared or are destroyed, and few alternatives come about. Masses transfer from the countryside to ever bigger cities (mega stables for humans, to express it in agricultural terms) without much perspective, and even with quite catastrophic consequences.

- And a world market for merchandises does not imply a world market for investments to be made, something which came much later, and which, moreover, was much hampered by imperialism, particularly in the form of autarkic

regions (like Russia, China, India, Pakistan and parts of Africa within the Russian capitalist bloc, together representing the great majority of the human population, locked up in ‘anti-americanism’); and the narrow-mindedness of even massive small scale solutions does not solve large scale, worldwide problems for the whole of humanity. regions (like Russia, China, India, Pakistan and parts of Africa within the Russian capitalist bloc, together representing the great majority of the human population, locked up in ‘anti-americanism’); and the narrow-mindedness of even massive small scale solutions does not solve large scale, worldwide problems for the whole of humanity.

Also see: Rosa Luxemburg.

de |  Die Akkumulation des Kapitals / Rosa Luxemburg. – Berlin SW61 : Vereinigung Internationaler Verlags-Anstalten g.m.b.h., 1923. – 520 S. – (Gesammelte Werke, Band VI) Die Akkumulation des Kapitals / Rosa Luxemburg. – Berlin SW61 : Vereinigung Internationaler Verlags-Anstalten g.m.b.h., 1923. – 520 S. – (Gesammelte Werke, Band VI)

de |  Die Akkumulation des Kapitals / Rosa Luxemburg. – Berlin SW61 : Vereinigung Internationaler Verlags-Anstalten g.m.b.h., 1923. – 520 S. – (Gesammelte Werke, Band VI) Die Akkumulation des Kapitals / Rosa Luxemburg. – Berlin SW61 : Vereinigung Internationaler Verlags-Anstalten g.m.b.h., 1923. – 520 S. – (Gesammelte Werke, Band VI)

de | Ökonomische Werke / Rosa Luxemburg. – Berlin [Ost] : Dietz Verlag, 1975. – 807 p. – (Gesammelte Werke ; Band 5)

Contains:

en | The Accumulation of Capital  / Rosa Luxemburg, translated from German by Agnes Schwarzschild, with a [highly uncritical] introduction by Joan Robinson. – London : Routledge and Kegan Paul ltd, 1951. – 475 p. – (Reprinted 1963, 1971) / Rosa Luxemburg, translated from German by Agnes Schwarzschild, with a [highly uncritical] introduction by Joan Robinson. – London : Routledge and Kegan Paul ltd, 1951. – 475 p. – (Reprinted 1963, 1971)

fr | L’accumulation du capital  (marxists.org; a source is not given, but it is from the following edition:) (marxists.org; a source is not given, but it is from the following edition:)

fr | L’accumulation du capital  / Paris : François Maspero, 1969. – (Œuvres, two volumes, downloadable in Word, pdf and rtf) / Paris : François Maspero, 1969. – (Œuvres, two volumes, downloadable in Word, pdf and rtf)

fr | L’accumulation du capital  / Rosa Luxemburg.– [Marseille] : Agone/Smolny, 2019. – 768 p. / Rosa Luxemburg.– [Marseille] : Agone/Smolny, 2019. – 768 p.

A new translation with new annotations

de | Programm der Kommunistischen Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands. – Berlin : Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands, Geschäftführender Hauptaussschuß, Januar 1924. – 47 S.

es |  El imperialismo y la acumulación del capital / Rosa Luxemburg, Nicolai Bujarin. – Córdoba, Buenes Aires : Ediciones de Pasado y Presente, 1975. – 251 p. – (Cuadernos de Pasado y Presente ; 51) El imperialismo y la acumulación del capital / Rosa Luxemburg, Nicolai Bujarin. – Córdoba, Buenes Aires : Ediciones de Pasado y Presente, 1975. – 251 p. – (Cuadernos de Pasado y Presente ; 51)

- Indica

- Advertencia v

- Rosa Luxemburg y su concepción del imperialismo / Peter J. Nettl xi-xxxv

- La acumulación del capital / Rosa Luxemburg 1

- [El problema en discusión] 3

- La crítica general de Bauer 43

- [Preliminares a la Critcia] 43

- [Las Condiciones economicas del crecimiento de la poblacion] 57

- El imperialismo y la acumulación del capital / Nicolai Bujarin 99

- Prefacio 101

- La reproducción ampliada en una sociedad capitalista abstracta 102

- Dinero y reproducción ampliada 128

- La teoría general del mercado y de la crisis 147

- Las raíces económicas del imperialismo 178

- La teoría del derrumbe capitalista 197

- Conclusión 207

- Apéndice

- El esquema de Marx de la reproducción ampliada / Kenneth J. Tarbuck 211

- La controversia sobre el derrumbe y Rosa Luxemburg / Paul M. Sweezy 215

- Comentario sobre la crítica de Sweezy a Bujarin / Kenneth J. Tarbuck 220

- El problema del imperialismo en Rosa Luxemburg / Kenneth J. Tarbuck 224

- Una apliación de la teoría de Rosa Luxemburg en la prediccion / Kenneth J. Tarbuck 232

- Notas 236

A lot of material for the debate on overaccumulation/overproduction can be found in Michael Roberts blog : Blogging from a Marxist economist  (by a leftist/trotkyist theoretician, yet one who does know the matter). (by a leftist/trotkyist theoretician, yet one who does know the matter).

en |  The early reception of Rosa Luxemburg’s theory of imperialism / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Gaido. – In: Capital & Class (Sage Publications); 37 (2013); 3; p. 437-455 The early reception of Rosa Luxemburg’s theory of imperialism / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Gaido. – In: Capital & Class (Sage Publications); 37 (2013); 3; p. 437-455

Source: Repositorio Institucional CONICET Digital  / Sage journals / Sage journals

es |  La teoría del imperialismo de Rosa Luxemburg y sus críticos: La era de la Segunda Internacional / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Gaido. – In: Critica Marxista (Xama Editora e Gráfica Ltda); 37 (2013), 10, p. 113-218 La teoría del imperialismo de Rosa Luxemburg y sus críticos: La era de la Segunda Internacional / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Gaido. – In: Critica Marxista (Xama Editora e Gráfica Ltda); 37 (2013), 10, p. 113-218

Source: Repositorio Institucional CONICET Digital  / Sage journals / Sage journals

en | Resumen

This article deals with the reception of Rosa Luxemburg´s "The Accumulation of Capital: A Contribution to the Economic Explanation of Imperialism" in the Second International before the start of the First World War. Our analysis shows that, if the condemnation of "The Accumulation of Capital" by the political right and centre was almost unanimous, its acceptance by the left was far from universal. In fact, both Lenin and Pannekoek rejected Luxemburg´s theory, adopting instead the economic analysis of an important spokesman of the centre, the Austro-Marxist Rudolf Hilferding. Our work concludes by analysing the reasons for those theoretical differences.

es | Resumen

El libro La acumulación del capital de Rosa Luxemburg, concebido con el fin de proporcionar una base teórica a la lucha contra el imperialismo librada por el ala izquierda del partido socialdemócrata alemán y, por extensión, de la Segunda Internacional, fue objeto de furiosas polémicas desde el momento de su publicación en 1913. Nuestra ponencia trata sobre la recepción de dicha obra en el seno de la Segunda Internacional antes del estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial, a la luz de los documentos recogidos en nuestro reciente libro Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I (Brill, 2012). Dichos documentos son presentados según su filiación política, centrándonos primero en las reacciones de los teóricos del ala centrista, nucleados en torno a Karl Kautsky en Alemania y a Otto Bauer en Austria, y luego en las actitudes de dos teóricos del ala izquierda de la Segunda Internacional: el ”tribunista” holandés Anton Pannekoek y el líder del ala bolchevique del Partido Obrero Socialdemócrata de Rusia, Vladimir Lenin. Nuestro análisis muestra que, si bien la condena a La acumulación del capital por parte de los centristas fue casi unánime, su aceptación por parte del ala izquierda distó de ser universal. De hecho, tanto Pannekoek como Lenin rechazaron la teoría del imperialismo de Luxemburg y adoptaron los análisis económicos de un prominente vocero del ala centrista: el austro-marxista Rudolf Hilferding. Nuestro trabajo finaliza analizando las razones de dichos desencuentros teóricos.

de | Zusammenfassung

Rosa Luxemburgs Buch Die Akkumulation des Kapitals, das als theoretische Grundlage für den Kampf des linken Flügels der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands und damit der Zweiten Internationale gegen den Imperialismus dienen sollte, war seither Gegenstand heftiger Kontroversen seiner Veröffentlichung im Jahr 1913. Unser Beitrag befasst sich mit der Rezeption dieses Werks innerhalb der Zweiten Internationale vor dem Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs im Lichte der Dokumente, die in unserem kürzlich erschienenen Buch Discovering Imperialism: Social Democracy to World War I (Brill, 2012) veröffentlicht wurden. Diese Dokumente werden nach ihrer politischen Zugehörigkeit präsentiert und konzentrieren sich zunächst auf die Reaktionen von Theoretikern des zentristischen Flügels um Karl Kautsky in Deutschland und Otto Bauer in Österreich und dann auf die Einstellungen zweier Theoretiker des linken Flügels der Zweiten Internationale : der niederländische „Tribunist“ Anton Pannekoek und der Führer des bolschewistischen Flügels der russischen Sozialdemokratischen Arbeiterpartei, Wladimir Lenin. Unsere Analyse zeigt, dass die Verurteilung der „Akkumulation des Kapitals“ durch die Zentristen zwar fast einhellig war, ihre Akzeptanz durch den linken Flügel jedoch alles andere als universell war. Tatsächlich lehnten sowohl Pannekoek als auch Lenin Luxemburgs Theorie des Imperialismus ab und übernahmen die ökonomischen Analysen eines prominenten Sprechers des zentristischen Flügels: des Austromarxisten Rudolf Hilferding. Unsere Arbeit endet mit der Analyse der Gründe für diese theoretischen Meinungsverschiedenheiten.

es |  Debates sobre La Acumulación del Capital de Rosa Luxemburg / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Fernando Gaido. – [s.l.] : Ariadna Ediciones; 2020; p. 267-294 Debates sobre La Acumulación del Capital de Rosa Luxemburg / Manuel Quiroga; Daniel Fernando Gaido. – [s.l.] : Ariadna Ediciones; 2020; p. 267-294

Source: Repositorio Institucional CONICET Digital  / Sage journals / Sage journals

es | Resumen

El presente ensayo analiza cómo Rosa Luxemburg desarrolló una visión propia sobre el imperialismo en su famosa obra, ”La Acumulación de Capital”. El trabajo analiza elementos de la trayectoria de Rosa Luxemburg que son relevantes para comprender este trabajo, el contexto de producción de la obra, sus planteos en relación a la acumulación de capital y el imperialismo y los debates que éstos suscitaron al interior de la socialdemocracia alemana y rusa, donde su obra no sólo fue rechazada por sectores de la derecha y el centro de la socialdemocracia, sino que también suscitó la crítica de militantes de la izquierda como Lenin y Pannekoek. El trabajo cierra analizando las respuestas de Luxemburg a sus críticos en la Anti-Crítica y analizando las consecuencias teóricas y políticas que estas discusiones tuvieron para la socialdemocracia internacional y el marxismo de la época.

de | Zusammenfassung

Dieser Aufsatz analysiert, wie Rosa Luxemburg in ihrem berühmten Werk „Die Akkumulation des Kapitals“ ihre eigene Vision des Imperialismus entwickelt hat. Die Arbeit analysiert Elemente von Rosa Luxemburgs Werdegang, die für das Verständnis dieser Arbeit relevant sind, den Kontext der Produktion der Arbeit, ihre Vorschläge in Bezug auf die Akkumulation von Kapital und Imperialismus und die Debatten, die diese innerhalb der deutschen Sozialdemokratie und Russland provozierten, wo ihre Arbeit nicht nur von Teilen der Rechten und der Mitte der Sozialdemokratie abgelehnt wurde, sondern auch Kritik von linken Militanten wie Lenin und Pannekoek auslöste. Der Aufsatz schließt mit einer Analyse von Luxemburgs Antworten auf ihre Kritiker in der „Antikritik“ und einer Analyse der theoretischen und politischen Konsequenzen, die diese Diskussionen für die internationale Sozialdemokratie und den damaligen Marxismus hatten.

Владимир Ильич Ульянов (Lenin)

Владимир Ильич Ульянов (Lenin) made a substantial contribution in 1915-1916 on imperialism; although he never gave any sign of having studied Marx’ Capital and did not express himself on the further questions elaborated here. We only give references here to the Internet Archive, where he is remarkably absent in French and Spanish.

de | Vorwort zu N. Bucharin: Imperialismus und Weltwirtschaft

en | Preface to N. Bukharin’s Pamphlet, Imperialism and the World Economy

de | Der Imperialismus und die Spaltung des Sozialismus

en | Imperialism and the Split in Socialism

it | L'imperialismo e la scissione del socialismo

de | Der Imperialismus als höchstes Stadium des Kapitalismus

en | Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism

it | L'imperialismo, Fase suprema del capitalismo

nl | Het imperialisme als hoogste stadium van het kapitalisme

en |  Marginal Notes on Luxemburg’s The Accumulation of Capital (1913) / V.I. Lenin. – In: Research in Political Economy, Vol. 18 (2000), p. 225-235 Marginal Notes on Luxemburg’s The Accumulation of Capital (1913) / V.I. Lenin. – In: Research in Political Economy, Vol. 18 (2000), p. 225-235

Source: Internet Archive

The Third International

On the First Congress of the IIIrd International in 1919 it was proclaimed that capitalism was, in somewhat ambiguous wordings (a “compromise” (and also a ‘shortcut’) between the Russian and the German Left, with different outlooks on fundamental questions), in its “death crisis”:

“The present period is that of the decomposition and collapse of the entire world capitalist system, and will be that of the collapse of European civilisation in general if capitalism, with its unsurmountable contradictions, is not overthrown.”

(Theses, Resolutions and Manifestos of the First Four Congresses of the Third International. – London : Ink Links, 1980. – p. 1)

Anton Pannekoek, in 1920, adhered to the argument, as he wrote:

nl | “Wat betekent dit alles? De Amerikaanse bankier Warburg heeft het aldus gezegd: Europa is bankroet. Hij spreekt als een kapitalist, voor wie het bankroet gaan van een collega iets heel gewoons is, waarbij het stelsel blijft; hier is het erger; het kapitalisme is bankroet. Niet in de afgezaagde zin, dat het innerlijk niet soliede is en eenmaal te gronde moet gaan, maar in de letterlijke zin; het kapitalisme als economisch stelsel staat voor zijn ineenstorting.”

en | “What does all this mean? The American banker Warburg has put it this way: Europe is bankrupt. He speaks like a capitalist, to whom the bankruptcy of a colleague is quite normal, whereby the system remains; here it is worse; capitalism is bankrupt. Not in the stale sense that it is internally not solid and must be destroyed one day, but in the literal sense; capitalism, as an economic system, faces its collapse.”

An ambiguity remained whether or not this applied to Europe alone, or to the planet as a whole.

At the Third Congress in 1921 this all too easy theory of collapse of a whole continent was abandoned and replaced by the idea that capitalism had gotten into a downward period, as expressed by Leon Trotsky  in a somewhat mind-boggling reasoning (and it was not specified whether this only applied to Europe alone or to the planet as a whole, including, for instance, the United States of America; and, as so often, he makes false, very ‘poetic’, analogies with natural sciences): in a somewhat mind-boggling reasoning (and it was not specified whether this only applied to Europe alone or to the planet as a whole, including, for instance, the United States of America; and, as so often, he makes false, very ‘poetic’, analogies with natural sciences):

de | „Der Aufstieg, der Niedergang oder die Stagnation – auf dieser Linie hat man die Fluktuation, das heißt die bessere Konjunktur, die Krise –, die sagen uns nichts davon, ob der Kapitalismus sich entwickelt oder ob er niedergeht. Diese Fluktuation ist das gleiche wie das Herzschlagen bei dem lebenden Menschen. Das Herzschlagen beweist nur, daß er lebt. Selbstverständlich ist der Kapitalismus noch nicht tot, und weil er lebt, so muß er eben einatmen und ausatmen, das heißt, es muß die Fluktuation vor sich gehen. Aber wie bei einem sterbenden Menschen das Ein- und Ausatmen anders ist als bei einem sich aufwärts entwickelnden Individuum, so auch hier.“

( Protokoll des III. Kongresses der Kommunistische Internationale, S. 73, see there for further argumentation.) Protokoll des III. Kongresses der Kommunistische Internationale, S. 73, see there for further argumentation.)

en | “Ascent, decline or stagnation – on this line you have fluctuation, that is, the economic activity, the crisis – they tell us nothing about whether capitalism is developing or whether it is going down. This fluctuation is the same as the heartbeat of the living person. The beating of the heart only proves that he is alive. Of course, capitalism is not dead yet, and because it is alive, it must breathe in and breathe out, that is, fluctuation must take place. But just as the inhalation and exhalation of a dying person is different from that of an upwardly developing individual, so here as well.”

Thus, Trotsky made a difference between a cyclical crisis and a crisis on the longer turn. There is no immediate death-crisis (an idea given up, although particularly the Essen Tendency stuck to it, and accused Trotsky of “treason”), but a general beginning of a long during capitalist decline, a position also Pannekoek kept defending, although he is not known for having referred to this congress, nor, in this respect, to Trotski. Trotski didn’t refer to Pannekoek neither, nor even to Marx’ Capital; and when a summary of Marx’ Capital (first volume only) was published, with Trotsky as the author, it turned out to have been written by Otto Rühle.

Here we will try to follow the debates, and, in time, to draw some conclusions.

The K.A.P.D.